THE CUSTOMER DISCOVERY FIELD GUIDE

Conduct Customer Interviews with Confidence

By

W. Scott Burleson

Palustris Publishing, 2025

Copyright © 2025 W. Scott Burleson

All rights reserved.

The unauthorized reproduction and distribution of this copyrighted work are illegal. Criminal copyright infringement, including infringement without monetary gain, is investigated by the FBI and is punishable by prison and extensive financial penalties.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews. For permission requests, contact the author at scottiob@gmail.com

ISBN

Cover Design by Palustris Publishing

Printed in the United States of America

First Edition

Table of Contents

CHAPTER 1: CONFIRMATION BIAS, THE ENEMY OF ACCURATE PERCEPTION.. 12

CHAPTER 3: CONDUCTING INTERVIEWS. 33

CHAPTER 4: ANALYZE RESULTS. 55

CHAPTER 5: COMMUNICATE RESULTS. 59

PREFACE

If you’re in product management, marketing, or innovation, you must develop customer interviewing skills. It is important to become a serviceable market researcher. This means that you can uncover, prioritize, and analyze customer insights.

If you’re further down this road as a professional market researcher, you probably already have a good foundation of customer interviewing skills. Still, I am confident you will find more useful tools for your box in this book. As practitioners, we quickly become comfortable with our methods. At some point, we often stop learning. My path to learning this craft began as a practitioner… as a product manager who suddenly needed to understand customer needs.

My first steps began when I took the Product Development and Management Association’s program to become a Certified New Product Development Professional. Their certification program was comprehensive. It introduced me to top authors and thought leaders. The course was my gateway drug, and I became an addict – pursuing a working knowledge of everything related to innovation. Of course, this included customer interviewing. According to PDMA’s research, inadequate customer knowledge was the leading cause of new product failure. Therefore, the importance of customer interviewing skills was obvious.

As a new product manager with John Deere, I did customer interviews early on. And I’m sure that I made every possible mistake. Deere had a great internal training program. They sponsored a course from Naomi Henderson, author of “Secrets of a Master Moderator.” She was a great instructor. Even to this day, I still have my tattered and highlighted notes. During this time, I found several other key references:

“The Voice of the Customer,” an article by Abbie Griffin and John Hauser (1993: Marketing Science)

Two books by Eduard McQuarrie: “Customer Visits” (Latest ed, 2014) and “The Market Research Toolbox” (Latest ed, 2015)

A book by co-authors Herbert Rubin and Irene Rubin: “Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data” (Latest ed, 2011)

During this time, John Deere had great internal market research experts. I learned much from Clarence Brewer, Tantina Hong, James Jeng, Frank Maier, and Bryan Zent. I took advantage of ample time to pick their brains and ask questions.

Deere also hired great market research firms. I tried to shadow these professionals, learning what I could. Ross Teague, a user-experience expert, was particularly good. Jan Johnson, with Millennium Research, was also a great practitioner. You learn a lot by watching the best at their craft.

However, in 2005, I read Anthony Ulwick’s book What Customers Want, in which he described his Outcome-Driven Innovation process. The ideas in that book changed everything. It was more than a research process; it was a philosophy. Soon after, I dug into everything Ulwick had written, which led me to Lance Bettencourt's work.

During the rest of my time with John Deere, I had the opportunity to plan and execute many Voice of Customer projects. I was getting better.

Ultimately, I joined Ulwick’s firm, Strategyn, in 2009. Suddenly, I immersed myself in a team of the world’s best innovation practitioners. In addition to Lance Bettencourt and Anthony Ulwick, there was a whole team of experts from whom I learned much.

After Strategyn, I joined my first B2B firm, Actuant. At Actuant, I developed and taught my Voice of the Customer course to global audiences in the US, China and Europe. This experience provided a harsh reality for some of the nuances of B2B innovation. I also had the privilege of taking a course titled “Listening to The Voice of the Customer,” conducted by Gerry Katz. Katz is a legend in the field, having published with Abbie Griffin and John Hauser, authors of the original “The Voice of the Customer” article. Also, during this time, I rounded out my credentials with the Market Research Certification Program through the University of Georgia, becoming a certified “Professional Market Researcher” through the Marketing Research Association.

Finally, my quest to understand a particular flavor of innovation, B2B, led me to Dan Adams, architect of the New Product Blueprinting system, a qualitative and quantitative method. It includes Voice of the Customer interviewing and much more. Ultimately, I joined Adams’ firm, The AIM Institute, where I have taught Voice of Customer, mentored hundreds of teams, and executed many client projects across diverse industries.

Overall, it’s been a 20-plus-year journey and an exhaustive education from the best. Even better, I’ve accumulated experience executing Voice of the Customer and using it to bring new products to market.

My intention with this book was to create a field guide. A book that brings together everything I’ve learned from so many people and experiences. I wanted it to be a reference, grounded in fundamentals, containing all the basics. At the same time, I wanted it to be as short as possible. A handbook without the frills of cases and stories. Instead, just stick to exactly what a practitioner needs to know.

For the rookie, an easy-to-understand, jargon-free guide covering all the bases. For the experienced, a complete method that provides new tricks. In either case, I hope this book will first honor all the great folks from whom I’ve learned so much. And second, it will serve as a practical handbook to all who seek to create better products through customer insight.

“Forget all the tools, frameworks, theory and start showing genuine interest in the other person, be it users, be it team members."

Beat Walther, Owner and Managing Director, Vendbridge AG

INTRODUCTION

Abbie Griffin and John Hauser's article “The Voice of the Customer” was published in 1993. It joined the fields of market research and new product development. It was built upon a product development method from the 1980s known as “Quality Function Deployment,” or QFD.

While QFD has fallen out of favor, the Voice of the Customer has not. Of course, modern practitioners still require a practical method to understand customer needs. And as it turns out, the basics are easy to understand. Anyone can learn these techniques—not just high-powered consultants or academics, but marketers, product managers, strategists and leaders. All can become effective practitioners.

What is Voice of the Customer?

Voice of the Customer is a market research process for gathering and prioritizing customer needs. The purpose is to learn.

Two Phases of Market Research

Voice of the Customer research has two phases. The first is the qualitative phase, which aims to uncover a complete set of customer needs. The second is the quantitative phase, in which we seek to prioritize that same list. This book is a guide for the qualitative phase, in which our key tool is the customer interview. “Qualitative " means that we’re not using numbers or statistics for analysis.

In this book, we stick to fundamentals. We will discuss five topics:

· Confirmation bias

· Preparation

· Conducting interviews

· Analyzing results

· Communicating results

Let’s begin with our biggest obstacle to learning: confirmation bias.

CHAPTER 1: CONFIRMATION BIAS, THE ENEMY OF ACCURATE PERCEPTION

“When men wish to construct or support a theory, how they torture facts into their service!”

Charles Mackay[i]

C. James Goodwin, in his book Research in Psychology, gave an illustration of confirmation bias as it pertains to extrasensory perception:

“Persons believing in extrasensory perception (ESP) will keep close track of instances when they were ‘thinking about Mom, and then the phone rang, and it was her! Yet they ignore the far more numerous times when (a) they were thinking about Mom, and she didn’t call, and (b) they weren’t thinking about Mom, and she did call.”[ii]

According to the American Psychological Association, “Confirmation bias is the tendency to look for information that supports, rather than rejects, one’s preconceptions, typically by interpreting evidence to confirm existing beliefs while rejecting or ignoring any conflicting data.”

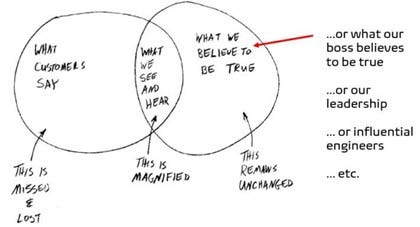

Confirmation bias makes people magnify information that supports their current beliefs, values, and opinions. But it’s even worse than that. This human frailty can prevent us from hearing information opposing our current position. We may not even hear conflicting information.

Confirmation bias reduces learning from the Voice of the Customer

Simply stated, we hear what we want to hear. We flush the rest.

We’ll discuss five strategies for addressing confirmation bias:

· Use a proven process

· Self-awareness

· Acknowledge your preconceptions

· Resolve to pursue the truth

· Expect this phenomenon in others

Each strategy begins with the assumption that all are vulnerable to confirmation bias. And therefore, we must mitigate its ability to cloud our judgment. Author Fred Alan Wolf stated, “In the Greek way of dealing with alchemy, which was earth, air, fire and water, these were the objective qualities. Within the objective qualities – things of earth, air, fire and water – are our subjective experiences of hot-cold, dry, and moist.”

This illustrates the dichotomy of two things. First, of truth. Truth exists. The next, our perception. Perception is the human attempt to perceive, measure, and assess this truth. Imagine that you touch something that is objectively, measurably, hot. The outer surface of a car in the summer sun. Your nerves take a measurement, send to the brain, where a neuron explosion begins a calibration. It’s hot. Not too hot to be burned, but uncomfortable. In some brains, that might be the end of the processing. Yet others might estimate how hot with a system of measures, such as Fahrenheit or Celsius. For greater precision, you use a thermometer. And there you have it, your perception along with an actual measurement.

If you were to do this many times, you’d improve your ability to access the temperature by touch. Unfortunately, when our brains, subject to the frailties of subjective assessment, are processing what we hear customers say, there’s no way to measure in order to compare and learn. Therefore, we must address confirmation bias.

For starters, we begin with a proven process. Good process itself will help to steer us from trouble in two ways. First, it prevents us from allowing our biases to influence what information the customer will share. The structure of an interview begins with open-ended questions. Moderators ask short questions leading to long answers. Moderators should speak little, while customers speak much. As the interview continues, Moderators will increasingly provide hints and direction. Next, good process prevents us from altering recorded notes by requiring note-takers to record verbatim statements. Otherwise, there’s an opportunity to filter, alter, and change a customer’s intent.

Next, we begin with self-awareness of what confirmation bias is. You don’t need to be a psychologist but be aware of your vulnerability to magnify agreeable statements. Normally, we can overestimate our abilities if we don’t understand the difference between our subjective assessments and the objective world. Think about bad contestants on talent shows who confidently and terribly belt out a song. They have no self-awareness of how bad they are. They believe they are quite good. With a huge gap between perception and reality, they are unable to make correct judgments about their talent. Therefore, we must begin with a self-awareness that our perception is only that: a perception. And we must accept that there will always be differences between what we think we hear and what was said. Or at least, the true meaning of what was said.

Next, acknowledge your preconceptions. Especially when using Voice of the Customer for product development, we often begin with a hypothesis of the customer’s challenges and even what the product should be. These are not “evil thoughts” and may even be close to the truth. And possibly making it worse, your interviewing team members also may hold these same ideas. All team members should write down these initial thoughts. Acknowledge them. And by so doing, accept that we do, in fact, have these ideas in our heads. This act, of acknowledging our preconceptions, will deprive them of a share of their influential power. It’s a similar idea to the first step of Alcoholics Anonymous, which is to admit that you have a problem.

Armed with this self-knowledge, resolve to pursue the truth. Decide that it’s best to learn the truth, regardless of your position. After admitting your preconceptions, you’ll find this to be a bit easier. You’ll be able to loosen your grip on what you believe the truth to be, a bit. Resolving to pursue the facts, you take on the mentality of a scientist. Naturally skeptical of your own beliefs. And instead, you’ll search for evidence that gets you closer to an authentic reality, whatever it turns out to be.

And finally, expect others to struggle with confirmation bias. You likely know something of their ideas, and so don’t be surprised when they exclaim how the Voice of the Customer is strangely proving them to be correct. They see what they want to see and hear what they want to hear. Without self-awareness, they are like the clueless talent show contestants. Fooling themselves into thinking that their perception and objective truth are, in fact, the same.

If possible, it would be helpful to walk other interviewing team members through a discussion of confirmation bias. Taking them through each of these five strategies. However, the bigger problem isn’t typically from the interviewing team. The real issues arise with confirmation bias when communicating results from VoC to others. The chapter on “Communicating Results” provides practical advice for this common situation.

CHAPTER 2: PREPARATION

“If you do not know where you are going, every road will get you nowhere.”

Henry Kissinger

There are six steps to prepare for a Voice of the Customer project. These are:

1. Establish objectives

2. Determine the customer’s Job-to-be-Done

3. Build a sample plan

4. Write questions

5. Organize questions into a discussion guide

6. Select interview contexts

First, we begin with our objectives and goals. If we don’t know our task, we have a poor chance of accomplishing it. Second, we determine what Job-to-be-Done that a customer seeks to do. The best Voice of the Customer projects lives within the intersection of our goals and our customers. Third, we define who those customers are within a sample plan. Fourth, we write questions. Fifth, we organize those questions into a discussion guide. Finally, we select the interview contexts.

Let’s begin by understanding our objectives.

1. Establish Objectives

Great preparation goes a long way towards a successful project. As you begin, work with your team to establish objectives. What are your goals? How will you use customer insight? What lingering questions are slowing down development? And more specifically, what are you seeking to do? What, precisely, will customer insight help you to get done better? Is the larger initiative about developing new products? Updating current ones? Is it about developing marketing strategies? Pricing strategies? Selling strategies?

Surprisingly, this is what most commonly fails to think through. Eager to get started, some just want to start interviewing as soon as possible. As a consultant, this is frustrating because the one thing that I’m not going to be good at is telling people what their goals should be.

By the way, we may be doing general exploration within a market. In this case, we may not have a tangible objective like “update a current product.” That’s perfectly acceptable. But it should be stated as such. In this situation, our project is about uncovering the “unknown unknowns,” as Donald Rumsfeld once spoke of when he said:

“Reports that say something hasn’t happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say that there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know we don’t know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tends to be the difficult ones.”[iii]

It is perfectly fine for the VoC goals to be about uncovering the “unknown unknowns.” But when doing so, let’s say so. We even have a name for this type of project: an exploratory project. This project is not directly tied to an internal product development or marketing initiative.

With that in mind, here’s a list of other typical initiatives:

· New product development

· Marketing strategy

· Mergers & Acquisition

· Concept testing

Regardless of what your purpose is, say it. You must know what job that customer insight will help you get done better.

Projects for the Voice of the Customer are usually team efforts.

2. Determine the customer’s Job-to-be-Done

To conduct a VoC interview, you need a topic of discussion. That topic will be the customer’s objective, goal, or larger problem to be solved. Thanks to the innovation literature of Anthony Ulwick and Clayton Christensen, we have a name for this objective: the customer’s job-do-be-done. Or, more simply, the customer job.

We call it a “job” because we use the metaphor that the customer is the boss. As the boss, they hire a product to help them do something. This metaphor accomplishes several things at once. First, it distinguishes a solution, which is what a customer buys, from the task it helps them do, which is why they buy it. They purchase a product to help them to do something. This “something” is their job-to-be-done.

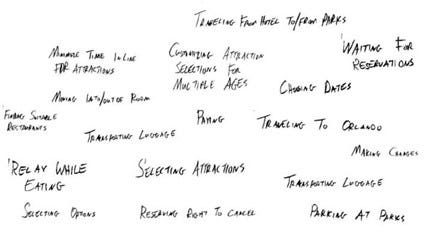

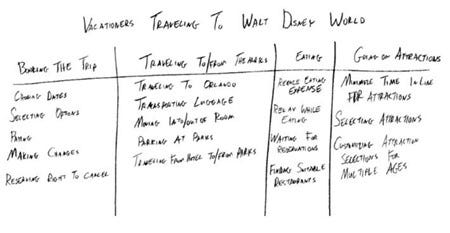

By defining a job for our VoC, we establish a scope for the customer conversation. Imagine that we’re studying the job of “traveling to Walt Disney World.” Our VoC questions will flow from this highest-level purpose to determine all the customers' challenges when traveling to Disney World.

Each interview question should help to illuminate this mystery. Shining light on a corner of the unknown within this job. Further, we also know what is out of scope. When the customer drifts outside the scope, the Moderator’s job is to bring them back. Of course, if we haven’t defined it, we cannot know when this has been violated.

The first step of our preparation was to clarify our internal objectives. We've defined the customer's objectives within the next step, defining the job-to-be-done. Our interview will live within the intersection of these two. Next, we specify who our customers are. We formally do this within a sample plan.

3. Build a sample plan

“Sampling” is a term from statistics. Consider that if we wanted to predict the outcome of a US presidential election, one method would be to ask every US citizen who they are voting for. This would provide reliable results. However, it would be expensive and time-consuming. Therefore, instead, we take a “sample.” We’d poll a subset of US voters, perhaps as few as several hundred. Based on their responses, we make a prediction.

A sample plan must represent the broader population

But how can the intentions of a few hundred voters provide a good enough estimate? Great question! And, especially concerning US election polls, there have been missteps. Mistakes have been made. Consider the following illustration as documented within The Statue in the Stone: Decoding Customer Motivation with the 48 Laws of Jobs-to-be-Done Philosophy (Burleson, 2020):

“In 1936, The Literary Digest polled its readers to predict the winner of the 1936 presidential election. Previously, their poll had correctly predicted the election results in 1920, 1924, 1928, and 1932. In 1936, 2.4 million potential voters once more weighed in. 2.4 million. With the power of this huge sample, The Literary Digest predicted that Governor Alfred Landon, of Kansas, would win.

However, Landon carried just two states – and of course – Franklin Delano Roosevelt won. Not only was The Literary Digest’s prediction wrong with a sample size of 2.4 million – but it was not even close. Roosevelt carried 46 states with 61% of the popular vote. Meanwhile, the Institute of Public Opinion made a correct prediction within 1% of the actual results using a comparatively small sample of 50,000.”

What went wrong? The Literary Digest’s sample was skewed. Even though the sample was outrageously large, it was not representative. The respondents were pulled from automobile owners. Additionally, all were subscribers to The Literary Digest. Both factors tilted towards higher income levels. So even with a sample in the millions, the survey couldn’t overcome this bias to make a good prediction.”

How do we avoid this sample problem? With a sample plan. It’s our strategy for how many and what type of customers to interview. It ensures representativeness.

A sample plan must include relevant diversity

A good plan helps us learn as much as possible from as few interviews as possible. Because, of course, we’re not going to conduct Voice of the Customer sessions with everyone. No more than we’d interview every eligible voter. Instead, we interview a sample. When structured well, this eliminates bias in our sample, and therefore, in our conclusions. How do we do this? By including relevant diversity.

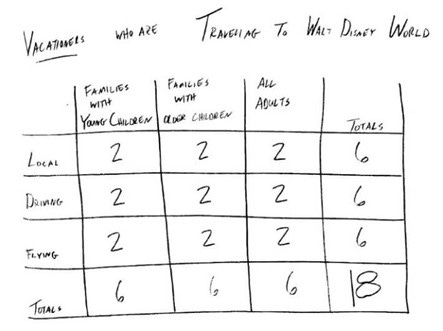

Consider an example. Imagine that you’re studying the market of vacationers traveling to Walt Disney World. (The job-to-be-done is “travel to Walt Disney World”) Consider what variables could cause customers to have different priorities to get started. Perhaps one might be the mode of travel to Orlando, FL. You could organize these into buckets of 1) local, 2) not local, but driving and 3) flying. Meanwhile, another variable might be group composition. You could have buckets of 1) families with young children, 2) families with older children, and 3) all adult parties.

Organize into a matrix, with quotas as follows:

In theory, you could consider many possible variables that could drive differences. However, the more we pick, the more difficult (and expensive) recruiting will become. Generally, focus on two primary variables, such as mode of transportation and group type. Other possible ones for the Disney World project might be:

· Number of times traveled to Disney World

· Age

· Preferred time of year for travel

· Income level

· Etc.

However, again, selecting too many variables for quotas will make recruiting difficult. This will make your VoC project more expensive and take longer. It’s usually best to focus on two axes. And for any other variables, just seek a mix.

Now that we’ve established your objectives, your customers’ job-to-be-done, and have a sample plan, it’s time to write questions.

4. Write questions

Customer interviews reveal insights. The interviewer's chief tool is the question, and questions are funny things. Consider this: When we ask a question, what happens to the dynamics of a room? Questions change things, don’t they?

Questions create tension.

This tension will not resolve until someone speaks, until there’s an attempt to answer the question. Any response will break the pressure. This is why, within the context of a conversation, we find silence to be so uncomfortable.

We will use this. Tension is good because it prompts customers to speak. However, it creates challenges because the discomfort can interfere with the customer’s ability to think and answer. It could also cause the customer to state what they imagine the interviewer wants to hear.

Therefore, we will ensure that the first and last questions are low-stress. Although for different reasons. We want the initial questions to introduce as little tension as possible to help the customer get into a “chatty” state. We want them to be comfortable and at ease, and we want them to forget about trying to say the “right” answer. The more comfortable and talkative the customer is, the more we learn. And again, everything about a proper Voice of Customer process is to maximize learning. We call this initial question type “Rapport-building.”

Once we have the customer talkative, we can get to our real topics of interest within our next type, “Objectives” questions. For these, we’ll get straight to it. Of course, they are called “Objectives” questions because they address our study objectives. They explore the customer’s job-to-be-done, helping us understand all the issues and pain points.

Finally, we’ll return to low-stress, low-tension questions. We call this last group “Wrap-up” questions. At this point, we have our data, and we want to leave on a positive note and express our appreciation while leaving the door open for follow-up later if needed.

Let’s look deeper into these general types: Rapport-building, Objectives, and Wrap-up questions.

Rapport-Building

It’s useful to think of a Voice of the Customer interview as a guided conversation. But not one between friends but a conversation between parties who don’t know each other well. Consider how any conversation goes between folks meeting for the first time. It’s unlikely that one would initially say, “So, what’s your religion?” Or… “What’s the most tragic thing that you’ve experienced?” In polite society, we don’t pose such personal questions to a stranger.

Then, how do we begin?

With strangers, we engage in “small talk.” Sharing tidbits about safe topics such as the weather or the changing seasons. Can you believe that summer is almost over? From there, you’ll transition into “safe” current events such as sports or mild news stories. Can you believe that the Patriots are in the Super Bowl again?

As we get to know our strangers better and they get to know us, we might ask slightly more personal but still safe questions.

We’re all familiar with this dance, and the steps are much the same for a Voice of the Customer interview. But because our purpose is to learn, we will script the initial questions to be informative while inducing as little stress and tension as possible.

Rapport-Building questions should meet these criteria:

· Low tension

· Easy-to-answer

· Relevant

We want to keep tension low with easy-to-answer questions at the start, making the customer comfortable and getting them in a chatty mood so that they’ll provide better information when we get to Objectives later. However, these questions also need to be relevant to the study. The customer knows this is a professional arrangement. They will have been told about the topic in advance; therefore, you’re going to induce anxiety if your questions seem off-topic.

Consider an example. Imagine that you work for a lawn equipment company. You want to build the next generation of lawn tractors and explore lawn care challenges. A good rapport-building question might be: Could you tell me a little bit about your property? This is a good question because it’s easy to answer. And because it’s also relevant. If you’ve been asked to participate in a study about lawn care, it’ll seem natural to begin by describing your property.

Further, the best rapport-building questions provide the interviewer with some reconnaissance. Providing helpful background for exploration later.

Objectives

Next, we have Objective questions. These relate directly to your objectives and the customer’s job-to-be-done. You design Objective questions to provide insight into your study’s purpose. However, we want to be crafty and even a bit evasive when writing them to learn as much as possible while revealing as little as possible.

All people bend towards consensus. When answering a question, we innately desire to provide an acceptable response, as we imagine what others want to hear. In other words, customers may tell us what they think we’ll find pleasing, and unfortunately, in our hearts, we also want them to tell us what we want to hear.

After all, we began the Voice of the Customer project with preconceived ideas about customer issues. As we’ve already explored, we’re subject to confirmation bias, which causes us to magnify things we believe to be true and ignore things we do not believe to be true. Therefore, when structuring our Objectives questions, we should intentionally seek the truth while preventing our bias from influencing customer responses.

SQLA

You’ve likely heard the Voice of Customer aphorism to “avoid closed-ended questions.” That’s a good start, but let’s expand on the concept and illustrate the importance. Instead of just open versus closed, consider the acronym “SQLA” for good questions. This stands for “Short Question, Long Answer.”[iv] I credit Naomi Henderson, author of “Secrets of a Master Moderator,” with this acronym. Short Question, Long Answer. Consider this as both criteria for writing questions and a mantra when conducting interviews.

The longer your questions, the more you’ll influence the customer’s response. With each additional spoken word, you reveal something, and likely more than you suspect. With more airtime, your body language and expressions will betray your intent to hide the inner workings of your brain, your true thoughts. Keep the questions short, and you’ll stay out of trouble.

Moreover, we prefer long answers from customers. The more they talk, the more they can sort out their true opinions, perspectives, and feelings. Watch someone answer a question. What’s their body language? They usually do not look the interviewer directly in the eyes. Instead, their eyes move to the left and move to the right. Often looking straight up. They may rub their chin or scratch the side of their face. When the brain is active, these are common movements searching for an answer. You want their full brain. You want access to the best information that they can recall and provide. If we keep them talking, we have a great chance to learn. But if we ask long-winded questions, not only do we overtly take up precious airtime and overly influence the process, but we signal to the customer that we’re not that interested in their response. Keep your main questions short and invite long answers. Remember SQLA.

Outcome-Driven Innovation Questions

Anthony Ulwick’s Outcome-Driven Innovation, or ODI, is an innovation process based upon jobs-to-be-done methodology. Beginning with a customer’s job-to-be-done, the interviewer probes about errors within three categories: Speed, Stability, and Output.

Within “Speed,” the Moderator asks what slows down the job. There are many ways to phrase the question about what slows something down. For example, for the job “Plan a Walt Disney World vacation,” the Moderator might ask, “What makes it time-consuming to plan a Walt Disney World vacation?” Time is a proxy for many issues. If something is difficult, it takes longer to do.

Within “Stability,” the Moderator is interested in what creates inconsistent results. They might ask, “When planning a Walt Disney World vacation, what can go off-track?” Or “… what might go wrong?”

Within “Output,” the Moderator searches for what restricts results. For example, they might ask, “When planning a Walt Disney World vacation, what limits the number of attractions you can visit?”

Within the categories of Speed, Stability, and Output, the Moderator can use a variety of probing questions, each intended to uncover an error.

Ask about Extremes

It can be enlightening to inquire about the best or worst experiences. When doing so, the Moderator should also explore to understand why. For example:

When taking a Walt Disney World vacation, what were some of your best experiences? What were some of your worst experiences?

Regardless of how they answer, the Moderator should probe to understand what made each positive or negative.

A vs. B

It’s helpful to ask customers to compare solutions.

For example, when planning a Walt Disney World vacation, why might you prefer to book the trip yourself rather than through a travel agent?

And then, ask in the reverse: When planning a Walt Disney World vacation, why might you prefer booking the trip yourself over a travel agent?

You’ll learn something different with each version of that question. And of course, probe for more reasons and more explanation.

However, you’ll likely also have specific questions. And you can ask those. Just be intentional when asking about specifics. More on this below during the “Organize questions into a discussion guide” section.

Wrap-up

Finally, we have wrap-up questions. These are simply transitions at the end of an interview, signaling that the session is nearly over. These should be light and easy.

When developing a new product, an example would be: If the director of engineering (or marketing) was here for this type of product, what advice would you give them? This is a good wrap-up question because it bucks the trend of going to narrower and more specific questions, as you’ll be doing at the end of the Objectives section. By backing out again to a higher level, it has the energy of a wrap-up question.

For our “travelers who vacation in Walt Disney World project,” you could ask, “Do you have any vacations of interest over the next year that you’re excited about?” This is a good question because we’re backing out of specifics. Signaling that the conversation is ending soon.

After a question or two like the examples above, I have a wrap-up question you can use for every interview, regardless of the topic: “Is there anything I didn’t ask about that you’d like to share?” Or, similarly, “Is there anything I didn’t ask you about, but I should have?”

Once you’ve written all your questions, it’s time to arrange them into a logical order.

5. Organize questions into a discussion guide

The Rapport-Building Section

Remember that this customer “interview” is really a guided conversation. This conversation (or interview) begins with your opening words to the customer. Just as when you meet any new person, inquire about safe topics. Is it snowy/hot/rainy where they are? The Super Bowl is coming up soon. Do they have a favorite? Feel free to offer a personal bit or two about yourself, something safe. The kids are back in school. You’re just coming off vacation, and getting back into rhythm is hard. The new puppy is destroying the furniture.

Offering a personal anecdote opens the door for your customer to do the same. If they engage, then go with it. If not, you may need to move onward with your Rapport-Building questions.

We’re trying to build a connection as best we can. The better the connection, the more that the customer will share later.

Return to the Rapport-Building questions you created earlier. Select 1-3 questions to use. If using more than one, sequence them from easiest to most difficult to answer. Although, by definition, all should be easy to answer.

The Objectives Section

In organizing your Objectives questions, you’ll have the most work to do compared to the others. Order them from the least-aided to the most-aided. The initial questions should be the most open-ended. The broadest. The shortest. And revealing the least.

As the interview continues, questions can become gradually more aided. Getting more specific and, finally, even revealing bits of your hypotheses. We organize in this way to avoid over-influencing the process. Further, this allows us to see if customers bring up certain topics independently. This presents the interview more as a “conversation.” Within the bounds of our scope and the broader questions, we allow customers to explore as they will.

Of course, customers may never bring up topics we’d like to discuss. No problem. We can still ask them. However, we will put these specific questions at the end of the Objectives session.

Consider this example. For our Walt Disney World project, we have a hypothesis that customers have problems when parking and walking into the parks. In this case, we might have four questions that we’d pose in this order:

· What are some challenges you’ve had when traveling to Walt Disney World?

· What issues do you encounter when going to the parks?

· What challenges arrive when driving your car to the parks?

· What issues have you had with parking?

Once you’ve parked your car, have you had any difficulties when walking into the parks themselves?

Note that each of these questions becomes progressively more aided. They begin open-ended so that the customer can easily respond in a conversational way to whatever their major issues happen to be. But as they continue, we get closer and closer to our hypothesis that there are challenges when parking and walking. By the way, if our hypothesis is correct, we may not even ask some of the latter questions. The customer might mention parking/walking even with our initial question, “What are some challenges you’ve had when traveling to Walt Disney World?”

Note that when customers bring up issues on their own, we will have higher confidence about the issue’s significance than when we bring them up instead.

The Wrap-up Section

The Wrap-up section of the interview is more about ending the conversation than learning anything significant. Ask your final couple of questions. Thank them for their time. And if applicable, let them know about any next steps.

6. Select interview contexts

Let’s begin with the most effective setting… the In-Context Interview.

Maximum Effectiveness: In-Context Interviews

You will learn the most when interviewing and observing customers within their environment. The one in which they interact with a product or are trying to accomplish their job-to-be-done.

Therefore, if we’re to study vacationers going to Walt Disney World, ideally, we’re right there with them. Interviewing them and observing them while they are actually on their vacation.

Imagine how much you would learn if you experienced the trip alongside the customer. The frustrations and pains. Watching the mother of a baby search for a place to nurse a little one. A family, with hurting feet, for two hours waiting for a ride. Exhausted adults, waiting in line, at the end of the day for a bus back to the hotel. Forgetting for a moment that this would be intrusive, it’s undeniable that you’d learn more about the challenges of a Walt Disney World vacation like this than any other way.

You’re no longer dependent upon their memories. With this approach, their responses are less likely to be altered by false or unreliable recollections. Also, less likely to be colored more strongly by experiences later in the trip than in the beginning.

Obviously, this has some drawbacks. More costly. More time-consuming. And it’s unlikely that customers will want you on their vacation with them. But make no mistake, we’d learn more in this way than any other.

Market research professionals call this “ethnographic research.” The term “ethnographic” comes from the social sciences. It implies that researchers embed themselves with their subject as if studying a foreign culture.

If In-Context sessions are both most effective and expensive. Let’s look at the opposite type, the fastest and least expensive… the Web Conference or Phone Interview.

Fastest and Lowest Cost: Web Conference or Phone Interview

Web Conference or Phone Interviews have obvious advantages. Fast and cheap, multiple could be done in a day. This, of course, comes at the cost of effectiveness since the web conference just can’t compete with a face-to-face, in-context session.

Interviews over web conferences are time savers when seeking the Voice of the Customer.

However, if you consider travel time, often involving flights, you could probably only do three in-context interviews on most weeks. Meanwhile, you could have done 10-20 web conference sessions that week. The difference is more than that, as a web conference interview can be set up with little notice, but a trip can take weeks to plan and do.

Another variable is the number of people to be interviewed at once. This brings us to the IDI (In-Depth Interview) versus group settings.

In-Depth Interviews (IDI) vs. Focus Groups

Another variable to consider is the IDI (either In-Depth Interview or Individual Interview) versus the Focus Group. The advantages for the IDI include:

· Learn more information per individual

· No group dynamics to manage

· Safer environment for the customer to share

· Lower stress

IDIs are easier than focus groups. And there’s no denying that you’ll learn more per person when that person has the floor for the entire conversation. Also, there’s more time for the interviewer and customer to bond, creating an ideal scenario for sharing.

Of course, Focus Groups are popular and have their advantages as well. Such as:

· Learn more per unit of time

· Customers build on each other’s ideas

· Can get feedback from multiple stakeholders at once

Undoubtedly, you’ll learn more in a 2-hour focus group than a 2-hour IDI. However, the focus group required more time for set-up and execution. You’ve had to arrange for a facility, and you’ve had to recruit multiple people. It’s also inevitable that you’ll get some “coasters.” Folks who are content to sit back and not share. This is most annoying when customers have been paid for their time.

One note regarding sample size… whether it’s an IDI or a Focus Group, each counts as “one” towards your sample total. If you have five in a focus group, that’s n=1, not n=5.

Finally, it’s often a good idea for the new market researcher to begin with the IDI approach. Then, build up your moderating abilities before taking on the extra complexity of managing a group.

Selecting Interview Contexts

In-person versus web conference? IDI versus focus group? What do you do? There’s no “right” answer for every project. Select the context that best fits your schedule and budget. However, with many projects, a mix often hits the mark, providing high-quality insight affordably and within a reasonable time.

CHAPTER 3: CONDUCTING INTERVIEWS

When conducting Voice of the Customer interviews, here are seven keys to success:

· Embrace a conversational mentality

· Avoid selling and solving problems

· Use distinct roles

· Know where a customer is a reliable (and unreliable) source of information

· Probe for understanding

· Take excellent notes

· Debrief immediately after the session.

To learn from our customers, it would be convenient if they had a USB input to their brain, from which we could download their needs. However, this is not the case; we, the interviewing team, must be the instrument.

Therefore, before a session, quiet your mind. For this short bit of time, don’t think about anything other than your customer. Consider breathing exercises or even listening to music. Drop everything mentally except for an extreme focus on the customer.

Don’t think too hard about what to ask next during the interview. If you’re doing this, then you’re not listening. Have you ever been conversing and had something you wanted to say, and you found yourself impatiently waiting for the other person to finish? That’s not the mentality of an effective Moderator. Instead, focus on the customer’s words. And more than that, listen to both what’s said and what they’re trying to communicate.

Customers often state the main point in their first few sentences. But not always. Sometimes, they need to talk it through. Give them space to explore if they’re on the right topic and are trying. The interview must be a safe place for the customer to pontificate.

Finally, embrace an extreme mindset of curiosity. Granted, some topics will be more compelling than others. You might be more interested in a project about Disney World than one about vinyl siding installation. However, there’s something interesting about everything if you bother to look for it. And do bother to look for it. Decide to be curious about the topic and the customer, and if you cannot manage that, it's better to find another Moderator.

Good listening is important to capture the Voice of the Customer

Embrace a conversational mentality

Think of an “interview” as a guided conversation. This isn’t the TV show “60 Minutes.” From the outside, it should appear as a conversation—just a chat in which one party (you and your team) happens to be quite absorbed in the other’s problems.

Just as when you meet any new person, you’ll begin with small talk—something about the weather or a safe topic. Ask them about their day. If they offer any personal tidbits, remember them and refer back to them if you can.

Call them by their name. People like that. It will endear them to you, and you’ll ultimately learn more.

Smile. Even if they can’t see you.

Think positive thoughts about the person. After all, you’re here to help them. Decide to be empathetic. Channel all the happy thoughts and positive energy that you can. Also, resolve not to judge anything the customer says negatively. Your role isn’t a judge. It’s to listen and learn. Be respectful, sensitive, and positive. Be appreciative of everything they share. It’s a gift. Treat it that way.

Silence is okay

If the room goes quiet, especially after asking a question, don’t rush to fill it with speaking. There’s a bit of panic amongst rookie interviewers during silent moments. But silence isn’t bad. It can be your friend. Ask the question and have the confidence to wait. Let the room be quiet. Someone will eventually speak. Let it be the customer.

If the customer can see you, use positive body language that says, “I’m comfortable.” Smile. If it makes sense, nod as if in thought. You’re giving your customer the gift of time, of patience. If you feel the pressure a bit, you might turn to scratch a few words on a pad. That can diffuse any discomfort as the customer sees you doing something… and give them time to collect their thoughts and respond further.

Release excessive control

Also, set aside your desire for excessive control of the dialogue. A conversation shouldn’t be controlled by one side. You’ve brought the topic for discussion. Maintain those boundaries, but otherwise, that’s control enough. This and your questions to keep things moving were your contributions. And even your questions are mere prompts to help customers articulate their needs.

Resist the urge to judge the session continually. And don’t let your colleagues judge it, either. We’ve established that a qualitative interview is a guided conversation. A conversation is a dynamic and living thing. We kill it when we overanalyze it minute-by-minute.

In practice, this can be worsened when a high-level executive is attending the session; however, if you happen to be an executive, first, good for you to read this book! But second, signal to your team that you are comfortable. Certainly, don’t take over the conversation. And if you can’t do this, know you’re destroying this valuable learning opportunity. If you can’t control your body language, then without a doubt, you shouldn’t attend these interviews.

Avoid sharing expertise

One more thing: check your ego at the door. This is not the time to display your expertise. In fact, by doing so, you’re likely to intimidate the customer into sharing less. This is difficult for many to do. We naturally want to share our expertise. We want to be perceived as knowledgeable. But let’s be clear: you aren’t interviewing your customers to show them how smart you are. You’re interviewing your customers to learn from them.

Some B2B innovators will protest, “But our customers expect us to know these things!” That may be true, but they also understand you’re interviewing them for their perspectives. However, if you feel so strongly that some questions sound “dumb,” then you can begin a question with something similar to, “This may be a dumb question, but I want to make sure that we don’t make any bad assumptions…” But most of the time, it’s just a person’s ego talking as they are afraid of appearing ignorant. Remember: make the customer feel like the expert, and they will tell you everything. Make them feel stupid, and they’ll tell you nothing.

There are two specific ways that moderators share their expertise with disastrous results: selling and solving problems.

Avoid Selling and Problem-Solving

Of all the ways to destroy the learning from a Voice of the Customer interview, the two most egregious are selling and solving problems. However, it’s easy to see how a Moderator might slip into these habits. After all, most VoC practitioners are not full-time market researchers. Instead, they’re in product management, marketing, or engineering in their normal life. Along the way, they’re expected to conduct VoC interviews for a new initiative, often to support new product development. Therefore, it’s natural that a person would behave as expected within their normal role. Fortunately, a little training (or reading!) can go a long way toward preventing these sins. Let’s take a closer look at each.

Selling. It destroys the vibe.

When we sell during an interview, it destroys the vibe of learning and the open exchange of ideas. The customer will immediately realize, “Oh, this is a sales call.” And because it is a normal sales call, they will be reserved in their responses. In a B2C situation, customers feel that pitch. Even worse, in B2B, customers believe the negotiation process has begun. Therefore, they’ll conclude that they should reveal as little as possible to maintain leverage.

It may not be obvious when selling begins to destroy the vibe of the meeting, and it might just look, sound, and feel like any other meeting. The customer shuts down and listens. And, of course, this is the opposite of what we want.

Do not sell during a Voice of the Customer interview. However, solving problems will likewise stop the learning.

Don’t solve problems.

When a customer shares a problem, and we suggest solutions, this appears to be productive. The customer may even appreciate the help. After all, they don’t have the learning goals we do, and they’d like their problems solved. But when we enter a problem-solving mode, learning stops. Not for the same reasons as when we sell, but it shuts down all the same.

Engineers especially feel this temptation. And it comes from a good place, wanting to be helpful. But resist this urge. Remember: you’re in the diagnosis phase of problem-solving. You are not in the solving mode quite yet. Use that problem-solving energy to push yourself to understand the issue as well as you can.

The time for solving will come soon enough!

Use Distinct Roles

Each person on your interview team will have one of four distinct roles: Moderator, Note-taker, Observer, and A-V person.

The Moderator

The Moderator conducts the interview and is, therefore, a required role. They follow the agenda and discussion guide while monitoring the time. The Moderator does most of the probing—nearly all, in fact. Importantly, the Moderator is the only person who should take the customer to a new topic or section of the agenda.

Truly, the most pressure is on the Moderator. They will bear the social weight of navigating the session. When customers are talkative, it’s quite easy. Moderators fan the flames and keep the fire burning. Throw on another log here and there. Wind the customer up and watch them go. And in truth, some interviews are just like that.

However, it’s the tougher situations where Moderators earn their keep. Some customers are naturally quiet, so that the Moderator must keep working to uncover more information. Sometimes customers will use a slightly different vocabulary, in which case the Moderator must translate while probing. Yet sometimes we have the worst challenge when customers claim not to have any problems at all, which is certainly not true. In which case, the Moderator must back up and try something new to get things going.

The Moderator role is exhausting. From the outside looking in, it’s difficult to tell why some interviews go well and others not as much. But there’s no doubt that great moderation skills are key for productive interviews.

The Note-taker

The Note-taker must begin with an understanding of how confirmation bias can alter the record and, therefore, the accuracy of the real insights. You’ve heard the phrase, “History is written by the victors.” Victors and journalists, who control information, can influence society with frightening efficiency.

Ask yourself a question: How successful of a general was Napoleon? After all, doesn’t everyone know he was an elite military leader? Maybe. Here’s something that might cast that into doubt. Consider that Napoleon closed all the newspapers in Paris except for four. Of these four, Napoleon owned two outright, and he censored the output of the other two. Through those channels, he shamelessly distributed propaganda about his military greatness and what happened on the battlefields.

As the Note-taker, you will not consciously thwart the truth, but confirmation bias can get in the way of accurate reporting. The Note-taker is the historian, and therefore, they must be careful to record accurately.

Especially when just getting started as a Note-taker, before building up your confirmation bias defensive muscles, it’s often a better idea to write verbatim notes as much as possible. The Note-taker can do this by capturing as many verbatim statements as possible. However, there will be times when they must listen and process. There’s a bit of subjective judgment in when to capture and when to listen. If in doubt, then keep writing all the customer’s words.

The Observer

The Observer is an optional role. However, this person can greatly improve the effectiveness of a session. Of course, the Observer carefully listens to the customer and the others. But along the way, they compare the customers’ statements to the notes taken and the Moderator’s probing questions. The Observer is keenly looking for what’s missed—the probing opportunities not taken, the notes not captured.

For a visual image of the Observer, imagine that the customer is on the roof of a house. He is throwing information off the roof in the form of candy. The Note-taker catches some, and the Moderator catches others. The Note-taker takes candy and records it. The Moderator takes candy and probes further. The Observer catches all the candy that is missed by both.

The “candy” will be customer needs that were either not recorded or were improperly probed upon. This raises the question, “When should the Observer bring these up?” Rather than bring them up on their own, it’s best for the Observer to be invited into the conversation by the Moderator. Suppose we have Mike, the Moderator, Nancy, the Note-taker, and Olivia, the Observer. In that case, Mike should occasionally turn to the Observer and ask, “Olivia, is there anything else that you had?”

There will always be something that was missed. As a bonus, this deferral to the Observer gives the Moderator a mental break from probing. Allowing them to catch their breath and consider where to go next.

The A-V person

The A-V person is also an optional role, but it is needed more when conducting contextual or ethnographic interviews. Their role is similar to that of the Note-taker, but instead of recording the interview with words, they record it with audio or video.

Obtain the customer’s permission before recording a session. If possible, get it even as you are setting up the appointment.

During the interview, the A-V person should be as unobtrusive as possible. If any set-up can be done before the customer’s arrival, it should be. The A-V person shouldn’t draw any attention to themselves. They should make their clothes and manner blend in as much as possible. Consider how wedding photographers and videographers take care to fade into the background. It’s the same principle.

Once the session is underway, the customer nearly always forgets about the recording process with these precautions. Therefore, it rarely impacts what information the customer will provide in practice.

Defer to the Moderator

Throughout the session, all defer to the Moderator. Otherwise, the customer becomes confused if team members are wrestling for control of the discussion. Also, during the Moderator’s probing, the destination of the questions may not be apparent to the rest of the team. Therefore, they may not realize the harm they’ve caused when jumping in with their question. When this happens, the Moderator’s line of inquiry is interrupted.

While it’s acceptable for the rest of the team to ask an occasional clarifying question, if in doubt, it’s best to let the Moderator do the probing.

Interviews to capture the Voice of the Customer are collaborative.

Know where the Customer is a reliable (and unreliable) source of information

When uncovering the Voice of the Customer, it’s important to know how reliable their feedback is. This assessment will change based upon the type of information they provide. When we ask a question, we’ll get an answer. But the problem is that there’s some information that customers are great at telling us—making them reliable sources—and other information types they are bad at telling us, making them unreliable sources.

The following distinctions are from The Statue in the Stone, Decoding Customer Motivation with the 48 Laws of Jobs-to-be-Done Philosophy. For more information on this reference, visit www.statueinthestone.com.

Where customers are reliable information sources

Customers are reliable sources about what they seek to accomplish

Customers, and all people, know their jobs-to-be-done. They know what their objectives are. Their goals. They know what they are trying to do. When gathering the Voice of the Customer, they are the expert as to their objectives.

Customers are reliable sources about any issues they are concerned about

Customers are aware of their worries. They know what errors, fears, and struggles concern them.

Customers are reliable sources about anything they have experienced

Of course, as people, we have memory limitations - and our perceptions can be untrustworthy. So clearly, “reliable” is a relative term. However, it’s indisputable that someone who has experienced something (such as traveling to Disney World) will be a more reliable source about the challenges than someone who has not.

When getting feedback for the Voice of the Customer, people are more reliable sources when describing their problems than accurately determining what solution would work best for them.

Where customers are unreliable information sources

Customers are unreliable sources about what solution best suits their needs

We have the famous quote from Henry Ford, “If I’d asked my customers what they wanted, they’d have said a faster horse.” This illustrates the fallacy. Customers are experts in their problems, not solutions to those problems. Therefore, when customers tell us what product or service they want, we should not take that idea too literally. This is a basic principle when seeking the Voice of the Customer.

So, what do we do when a customer requests a product or feature?

This is not a situation to fear. It presents perhaps the easiest probing opportunity. We want to learn why the customer thought this product idea would help them. If they ask for a faster horse, we respond with something akin to the following:

· How would that help?

· What would that help you to accomplish?

· Why would you want that?

Notice that with these questions, we’re moving from where the customer is unreliable (their requested product) to where they are reliable (what they seek to accomplish - or - any issues/concerns they are concerned about).

Customers are unreliable sources about where a product is over-performing

How can you tell if your internet speed is too fast? You can’t. Once past a threshold of instant response, you have no idea how far past that point the service is. Notice the commonality with the “interviewing mentality” section above. This is why during probing, it’s more useful to focus on problems rather than things that are going well.

Customers are unreliable sources about anything they’re not interested in

When gathering the Voice of the Customer, we will have difficulty learning anything outside of the customer’s interest. However, this shouldn't be a problem if the sample plan is designed well.

Probe for Understanding

The most interested Moderators ask the best probing questions. After all, we will never know exactly where a customer may go or what they’ll say. If the Moderator embraces their curious spirit, they will find a path forward. And quite frankly, they are probably in the wrong role if they are not attentive to the customer’s concerns. Not just as a Moderator but as a member of an innovation team. However, here are five “out of the box” Moderator gambits: 1) Push to the outcome statement, 2) Imagine that you have to solve it, 3) Repeat the customer’s thoughts, 4) Push for visualization, 5) Ladder up and down, 6) Clarify vague benefits, and 7) The universal probing question

Probing Gambits

Push for a metric

When the customer is describing their difficulty, probe to see how they might measure the quality they desire. For example, imagine the following scenarios within our Disney World example:

Customer: Parking can be difficult at times.

Moderator: Difficult? In what way?

Customer: Difficult to find a good parking spot.

Moderator: How might you evaluate a good versus bad spot?

Customer: With a bad spot, it means a longer walk to the park.

Moderator: Is more about the effort required to walk into the park, or the time?

Customer: Time for sure. It’s an expensive trip and you want to spend your time in the park. Not walking to it.

Moderator: So, you’d like to minimize the time to walk from your car into the parks?

Customer: Yes.

And another example:

Customer: I tend to avoid the faster rides.

Moderator: What is it about the faster rides?

Customer: I don’t feel so great a few minutes into them.

Moderator: You don’t feel well? In what way?

Customer: Motion sickness.

Moderator: I see. With the faster rides then, you’d like to minimize the likelihood of motion sickness, is that right?

Customer: Yes.

In both of these scenarios, as the Moderator probes to better understand the problem, he is acutely listening for something measurable. The first instance revealed the challenge was about time—the time to travel from the parked car into the park. By the way, time is the most common metric as it covers a multitude of difficulties. The more difficult something is, typically, the longer it takes.

In the next scenario, the customer began by complaining about faster rides. The moderator probed further to understand the nature of the difficulty. Notice that the moderator didn’t begin a series of yes/no questions. Do the faster rides give you headaches? Do they make you fearful for your safety? Do you avoid the faster rides because you’re worried about losing items such as sunglasses?

It’s not the end of the world to ask these yes/no questions, but they are inferior to probing without suggesting examples. As soon as the customer mentioned “motion sickness,” the Moderator recognized that the metric was “likelihood,” which is the probability of getting motion sickness.

Note that the Moderator confirmed they had the correct metric in both scenarios before continuing.

Sometimes, it can be helpful to ask the customer, “How do you measure that?” or similar as follows:

Customer: I wish the parks had healthier food.

Moderator: Interesting. I’m curious, how would you measure the healthiness of food?

Customer: Mainly the calorie count. I mean, you’re on vacation so you’re going to eat snacks. But all the fried food is so high in calories that it can get away from you quickly.

Moderator: I see. You’d like to increase the number of low-calorie snacks available.

Customer: Yes.

By directly asking, “How would you measure the healthiness of food? " The moderator receives a direct answer… “the calorie count.” Without this clarity, the moderator might have left the outcome statement as “Increase the likelihood of finding healthy food choices.” However, the customer revealed that they had something specific in mind: low-calorie food. They weren’t as concerned about nutritional density, issues with genetically modified food, carcinogens, percent of healthy fats, glycemic response, etc.

The customer, quite specifically, wants low-calorie food options so they can enjoy more of it! By pushing for a metric, something measurable, the Moderator learned exactly what the customer needed.

As with many concepts in this book, pushing for a desired outcome, which contains a metric, is direct from Ulwick’s classic, What Customers Want.

Imagine that you have to solve it

When a customer describes a problem, imagine that you are going to solve it immediately. What information do you need to solve it well?

Imagine the following dialogue with our Disney World vacationer:

Customer: I don’t sleep well in the hotels.

Moderator: Worse than at home?

Customer: Yes.

Moderator: What do you attribute that to?

Customer: Lots of things, probably.

Moderator: Sure. What might some of them be?

Customer: We get to the room pretty early. But the late goers are returning all hours of the night. They can be quite loud.

Moderator: What time do you like to go to bed?

Customer: Around 9:00.

Moderator: Sure, understood. What else might make it difficult to sleep?

Customer: We’ll often have a neighbor watching television. Quite loud.

Moderator: For how long?

Customer: Often all night.

Moderator: Yes, I can see how that would be distracting. What are some other issues that might interfere with sleep?

Customer: The children are often wired from the day. It’s hard to settle them down. Sometimes, we’ll let them watch a movie but then that keeps everyone else up.

Moderator: I see. It’s hard to have entertainment for a couple that doesn’t distract everyone else.

Customer: Exactly.

The customer began with what seemed to be a simple enough problem. We might have even grabbed an outcome statement from the customer’s initial comment, “I don’t sleep well in the hotels,” with “Minimize the likelihood of poor sleep quality when staying there.” However, by imagining that we have to solve the problem, we’re pushing for root causes. And look at the diversity that was uncovered:

· Loud folks returning from the parks

· Neighbors blasting their televisions

· Children too wired to sleep

By the way, did you notice that even though the customer complained about the neighbors watching television late into the night, our customer did the exact same thing to settle the children down?

If we pretend that we will solve the problem, it naturally points us to uncover root causes. Further, this perspective helps us know “how much” detail we need.

Repeat the customer’s thoughts

One probing tip is to repeat the customer’s thoughts back to them… but as a question. For example, imagine this dialogue with our Disney World vacationers:

Moderator: What challenges do you have when traveling to Walt Disney World?

Customer: It’s hard to find healthy food in the parks.

Moderator: It’s hard to find healthy food in the parks?

Just repeating their words back to them as a question invites them to elaborate in a way that reveals no bias while also showing respect. Do so in an inquisitive way, with the last syllable going up. This is something that we all understand from normal conversations.

Visualization

Try and visualize the customer’s challenges. This will push you to use your senses to better understand what’s going on. Imagine this dialogue:

Customer: I don’t enjoy the bus service to the parks.

Moderator: When you’re on the bus, what do things look like from your perspective?

Customer: If I’m standing, then I have to touch those public rails so as to not fall. I’d rather not do that.

Moderator: What else is challenging about standing?

Customer: You get slung around when the bus turns. Not that comfortable.

Moderator: What does this look like? Help me to visualize this experience.

Customer: I’m holding on to the rails. And there’s usually someone else’s kid just a step away.

Moderator: How does that present problems?

Customer: You want to give people space, but children may not understand that.

Moderator: What else? What else to you see or hear that can create an issue.

Customer: Coughing.

Moderator: Coughing?

Customer: Yes. We’re in close quarters. Tired after a long day, and you’ll have folks coughing and you really can’t escape it.

Moderator: The germs?

Customer: Yes, exactly.

The moderator could continue to explore in this way: asking the customer to describe what he sees. By the way, you could use other senses as well: What does the customer hear, smell, feel, etc.?

Clarify vague benefits

We cannot be contented with vague need statements when seeking to understand the Voice of the Customer. For example, some typical culprits:

· Easy to use

· Durable

· Reliable

· Simple

· Flexible

· Comfortable

Vague words such as these create the illusion of clarity. After all, when someone says they want their product to be “easy to use,” they know what they mean. However, if our note-taker writes down “easy to use” as the need and we leave it there, we haven’t truly captured much of anything. Instead, we have a vague phrase that, like art, will take a different meaning within the minds of those who see it.

Addressing vague benefits

Here’s the good news. We'll know how to respond when customers offer these nebulous terms. Ask them to define the opposite. For example, if one says, “I want my new product to be easy to use.” Then reply, “What makes it difficult to use?” If they say, “This process should be simpler,” reply, “What makes it complicated?” For our Disney World travelers, if they say, “I’d like for my vacation arrangements to be more flexible,” then reply, “What would make them inflexible?”

Hopefully, you’re starting to see commonalities for understanding the Voice of the Customer. And it’s not enough to capture what the customer believes to be correct; we must also capture it so that it can be correctly interpreted later.

Ladder up and down

When probing, “laddering” is zooming in or out. We “ladder up” to understand a problem's implications, and we “ladder down” to understand its root causes.

Ladder up to understand “Why?” Ladder down to understand root causes. By “laddering” up and down, we’re gathering critical insights for the Voice of the Customer. Insights that will be useful when innovating later.

Ladder up to understand the implications

Within our Walt Disney World example, imagine that our customer replies that “It takes a long time to find a parking space.” Our Moderator could ladder up. It sounds like this, “How does this impact you?” or “Why is this a problem?” Perhaps they replied, “This means I have to spend more time in transit when I just want to enjoy the parks.” As the Moderator, you could ladder up again: “And how does that impact you?” To which the customer might reply, “It becomes frustrating, knowing that I’m not getting as good of a value.”

The more you ladder up, the more you approach emotional rather than functional needs. The more you ladder down, the more you expose potential root causes.

Ladder down to understand the root causes

A key reason to seek the Voice of the Customer is to create new products and services. New offerings that address problems. To solve them, we must first understand the root causes. To understand the sub-problem that contributes to the larger one. When presented with the same statement, “It takes a long time to find a parking space,” laddering down sounds like:

· What contributes to this?

· Could you describe some of the root causes?

· What makes this worse?

· To this, the customer might say any of the following:

· The parking lots are so large, and you spend much time searching for that rare open spot.

· Most people arrive at the parks at the same time.

· Parking attendants are sometimes missing.

· My children are excited and loud, making it difficult to focus.

To solve a problem, we must first understand the contributing factors. A solution for missing parking attendants would be quite different than one to help with many park-goers arriving at the same time. Likewise, the answer would be different if addressing the distraction of excited children.

The universal probing question

There is one probing question that works all the time. As in, 100% of the time and in all circumstances. The question is this, “Can you tell me a little more about that?” It’s a nice probe to have in your back pocket when stuck.

How far to probe?

You may find yourself wondering, “How much should we probe?” To understand how far to go, imagine that you will immediately move to solve problems after the interview. Do you understand it well enough to solve it? If not, keep going.

Take excellent notes

It should be obvious that we need confidence in the notes when documenting the Voice of the Customer. Churchill quipped, “History will be kind to me, for I intend to write it.”

Let’s recall how this field guide on the Voice of the Customer began warning about confirmation bias. This is a force that threatens everything we do. So that we magnify bits that we believe to be true and diminish bits that we disagree with. Leaving us with a comforting story rather than the truth.

Therefore, our Note-taker must become hyper-aware of this tendency. But even more, here are other strategies to ensure we can trust the interview notes.

First, the Note-taker should capture verbatim comments as much as possible, as we can’t get into too much trouble when writing exact words and phrases. However, when the Note-taker stops, listens, and summarizes... you can bet that they’ve added their interpretation of the story.

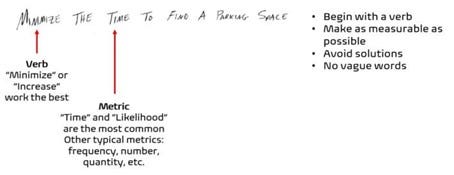

Next, consider working with the customer to craft Desired Outcome statements created by Anthony Ulwick. To thoroughly treat this idea, read the classic innovation book What Customers Want. Ulwick’s Outcome-Driven Innovation provides a template for a customer need in the form of a desired outcome. It begins with a verb (usually minimize) and has a metric and a contextual clarifier. Work with the customer to get the outcome statement correct. It turns out that questions that lead to desired outcomes happen to be good probing questions. But what might this look like? If our Disney travelers complain about it taking a long time to find a parking space, we might convert that to an outcome statement such as, “Minimize the time to find a parking space.”

Translate the Voice of the Customer into a Desired Outcome statement

It takes time and practice to learn to create desired outcome statements. However, it’s worth the effort. You end up with something unambiguous and stable that accurately reflects the Voice of the Customer. These statements can be easily used within a survey or similar prioritization method.

Debrief immediately after the session

Every principle for understanding the Voice of the Customer helps address the same objective: learning. To that end, it’s critical to debrief immediately after conducting your interview.

It’s tempting to omit this step. Hey, let’s get together when back in the office. Let’s connect on Monday. However, if you wait even a single day, you’ll have forgotten much of what you heard. According to the “Ebbinghaus forgetting curve,” people forget about 50% of what they learn within a day. However, if they recall and review within 24 hours, this “forgetting” can be as little as 20%.[v]

Additionally, the Voice of the Customer is a multi-player activity. Nearly always, the interview will be conducted by a team of 2-4 people, perhaps more. Therefore, when reviewing right after the interview, it’s unlikely that anything will be missed or forgotten among all the team members.

What do you do during the Debrief?

The team will discuss themes from conclusions within this recent interview and others. During the debrief, you’ll review notes - both the “official” ones and those of the Observer and Moderator. The truth emerges as the collective song from many sessions. Across the scope of your project, patterns emerge.

Analyzing results should be a team effort, which is critical to reducing bias when drawing conclusions for the Voice of the Customer.